Conscription by poverty: Deprivation and army recruitment in the UK

This applies to army recruitment in pretty much every country around the world that has an active military, including Canada and the United States.

Introduction

Each year the British armed forces enlist over 2,000 children aged 16 and 17, mostly for the army and particularly for the infantry; more new army recruits are 16 than any other age. The United Kingdom (UK) is the only State in Europe and among only a few worldwide allowing enlistment at age 16.

Recruits are no longer routinely sent to war until they turn 18, but the impact of military employment at a young age, particularly on recruits from a stressful childhood background, has raised numerous human rights and public health concerns. Among those to express concern have been the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, the children’s commissioners for the four jurisdictions of the UK, and the Joint Committee on Human Rights

Young army recruits tend to come from particularly deprived backgrounds

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) does not collect information about the

socioeconomic profile of armed forces personnel. Nonetheless, our research

has found that army recruits under the age of 18 come disproportionately

from England’s poorest constituencies. During a five-year period, the rate of

recruitment in the age group was 57 percent higher in the most deprived fifth of constituencies than the least deprived. Recruitment was concentrated in the poorest regions, particularly urban fringe areas of the north of the country.

Research by King’s College London further shows that a troubled childhood is common among army personnel (irrespective of age), while official data show that the youngest recruits tend to have severely underdeveloped literacy. Childhood adversity and poor literacy are both well-attested statistical indicators of socioeconomic deprivation.

The army focuses recruitment in the poorest parts of society

Using official sources, our research has shown that army recruitment is

targeted at the UK’s poorest towns and cities, particularly neighbourhoods

where annual family income is around £10,000.

The army targets the youngest age group for the riskiest army jobs

The army’s rationale for targeting 16-year-olds for recruitment is to

compensate for shortfalls in adult recruitment, “particularly for the infantry”;

the close-combat troops. Its own research confirms that a lack of economically viable civilian opportunities is one of the main factors driving enlistment for the infantry, which can be joined without any qualifications. The army’s youngest recruits are therefore substantially over-represented there.

The infantry carries the greatest risks in war. In Afghanistan, British infantry troops were six times as likely to be killed as personnel in the rest of the army, and in the Iraq and Afghanistan era, they were twice as likely to experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Relative to the rest of the army, infantry training is basic and, according to veterans, more brutalising, with twice the drop-out rate among trainees, at approximately 35 percent.

on the subjugation, abuse and exploitation of men

who become soldiers out of desperation.

to make rich men richer while they kill off all the young male competition.

on the subjugation, exploitation and abuse of women in 1%er culture

Most outlaw motorcycle clubs do not allow women to become full-patch members.[37] Rather, in some 1%er clubs, women have in the past been portrayed as submissive or victims to the men,[38] treated as property, forced into prostitution or street-level drug trafficking, and often physically and sexually abused,[39] their roles as being those of obedient followers and their status as objects. These women are claimed to pass over any pay they receive to their partners or sometimes to the entire club.[40] This appears to make these groups extremely gender-segregated.[41] This has not always been the case, as during the 1950s and 1960s, some Hells Angels chapters had women members.[42]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outlaw_motorcycle_club#One_percenter

The elusive Gerald Murray

Also known as Thomas Murray.

Rise of motorcycles after World War II

After World War II, countless veterans came back to America and many of them had a difficult time readjusting to civilian life. They searched for the adventure and adrenaline rush associated with life at war that had now left them. Civilian life felt too monotonous for some men who also craved feelings of excitement and danger.[3] Others sought the close bonds and camaraderie found between men in the army.[6] Furthermore, certain men wanted to combat their horrifying war memories and experiences that haunted them, many in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder.[7] Thus, motorcycling emerged stronger than ever as a substitute for wartime experiences such as adventure, excitement, danger and camaraderie.[3] Men who had been a part of the motorcycling world before the war were now joined by thousands of new members. The popularity of motorcycling grew dramatically after World War II because of the effects of the war on veterans.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollister_riot#Rise_of_motorcycles_after_World_War_II

funneh

In 1948, the AMA supposedly made a statement that ninety-nine percent of the motorcyclists are good people enjoying a clean sport and it is the one percent that are anti-social barbarians. The term “one percenter” is born.

Hell’s Angels

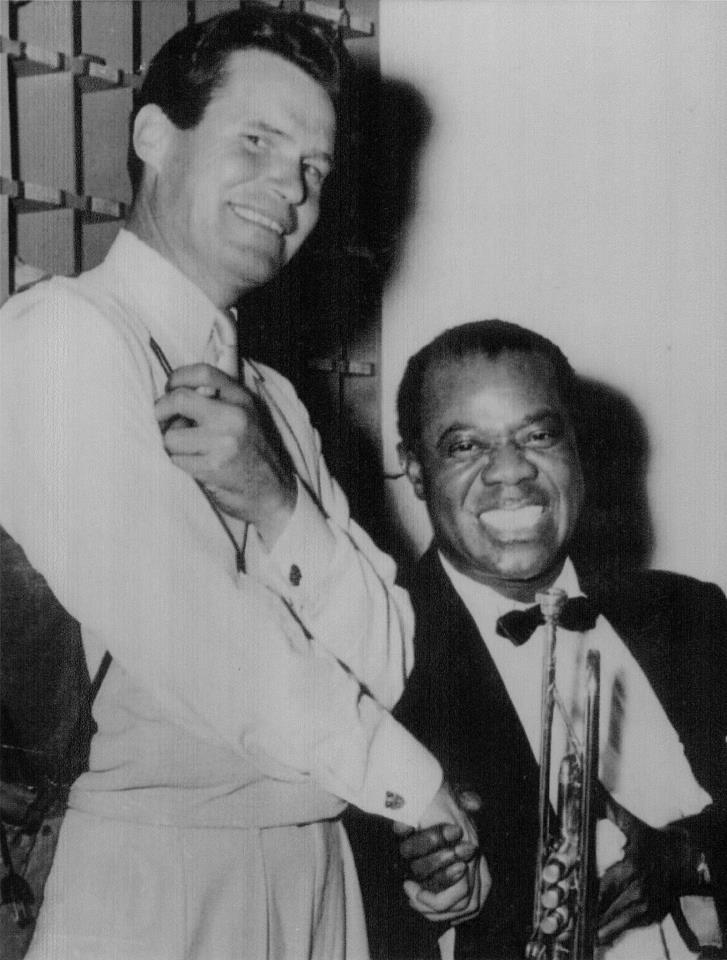

During the War, the 303rd flew 364 missions, more than any other Eighth Air Force B-17 group, and one group Fort, “Hell’s Angels”, was the first to complete 25 missions, while another, “Knock Out Dropper”, was the first to complete 50 and 75 missions. Only one other group delivered more bomb tonnage than the 303rd. However, the group lost 165 planes, more than five times its authorized strength of 30 B-17s.[1]

The Hells Angels originated on March 17, 1948 in Fontana, California, when several small motorcycle clubs agreed to merge.[7] Otto Friedli, a World War II veteran, is credited with starting the club after breaking from the Pissed Off Bastardsmotorcycle club over a feud with a rival gang.[8]

The name was first suggested by an associate of the founders named Arvid Olsen, who had served in the “Hell’s Angels” squadron of the Flying Tigers in China during World War II.[10] It is at least clear that the name was inspired by the tradition from World Wars I and II whereby the Americans gave their squadrons fierce, death-defying titles; an example of this lies in one of the three P-40 squadrons of Flying Tigers fielded in Burma and China, which was dubbed “Hell’s Angels”.[11]

snap, crackle and pop!

Bernice Cloutier and Gordon Murray

Raised in foster care, away from my family, I’m only learning about my family history now. Turns out they’re nowhere near as bad as my foster mother made them out to be, not even remotely. Wish I had the chance to get to know them better before they passed away.

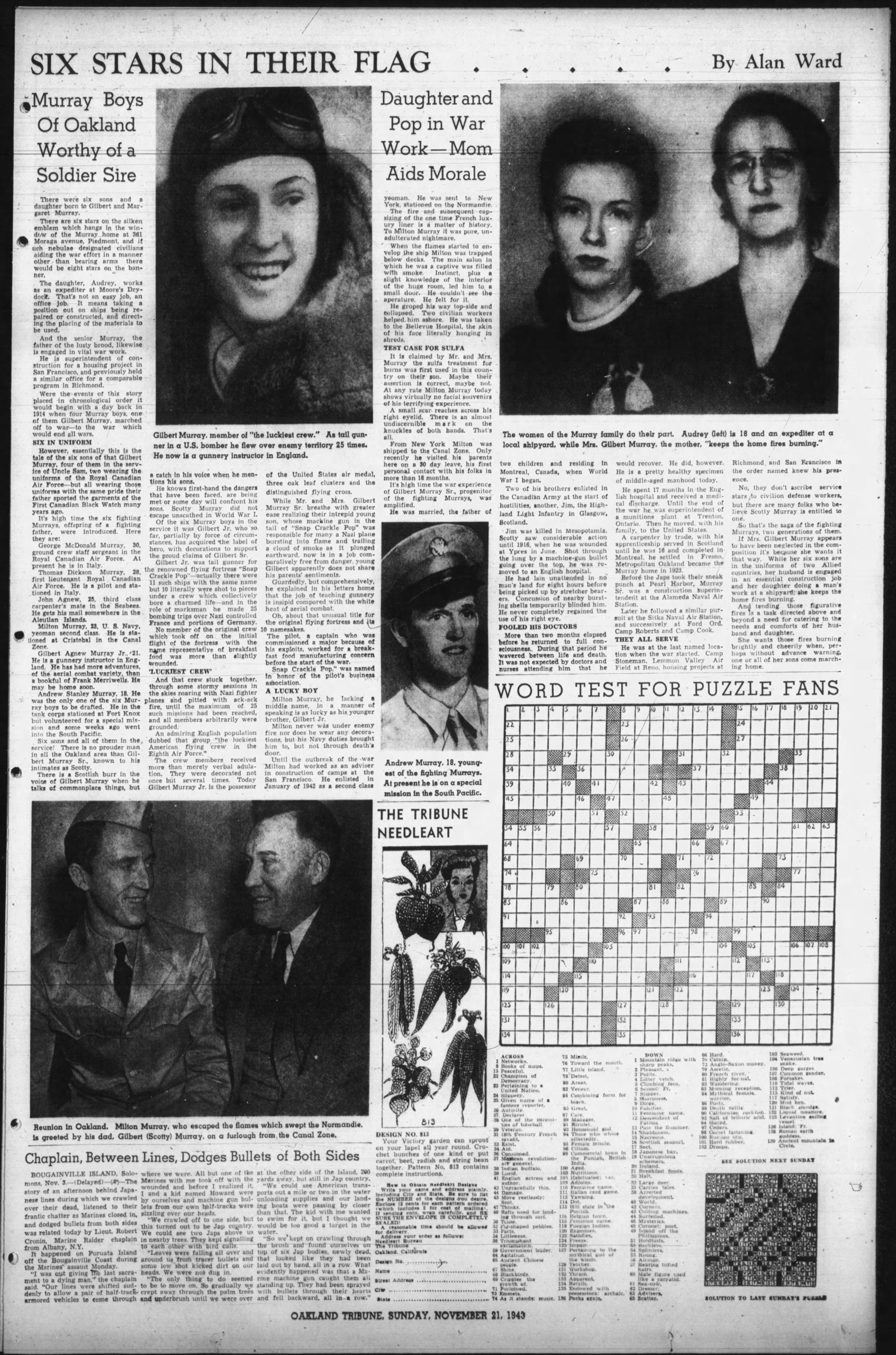

Murray Boys of Oakland, California

Murray branch of the family in California. Gilbert (Scotty) Murray is my great grandfather’s brother, my great grand uncle.

My grandfather Gordon’s twin brother Douglas was killed in WWII, devastated him, he never got over it, wore his dog tag for the rest of his life.

It’s possible my grandfather’s brother Thomas is my biological grandfather as there is some rumour that he coerced my grandmother when she was drunk… or maybe it was consentual. I’m not sure, it’s a sensitive topic for other members of the family and they don’t want to discuss it. I DO want to discuss it so we all know what actually happened because my mother was abused as a result of all this, which subsequently landed my brother and I in foster care, which my family also does not want to discuss.

Lots of not wanting to discuss anything in my family, on both sides of my family. Before I found out the trauma (both sides of) my family experienced not just in WWI and WII but going back over many generations as soldiers, losing your brothers and fathers and family members to senseless greedy wars will warp a family after awhile. Creates dysfunction, family alienation, complete family breakdown.

I understand all this now.

But I still want to know what happened.

Knowing your family history is important.

noise pollution, light pollution and elbow room

there is a street light right outside my bedroom window that floods my backyard with artificial light all night long, it’s terrible. it also seems to be affecting plant growth in my yard. so does soil quality. water quality as well. we had our water tested a couple of months ago and it’s as bad as Flint, Michigan. we have a problem with lead poisoning in Montreal, especially the oldest neighbourhoods. buildings in my hood are selling for millions now, displacing renters, and these new millionaire home owners are drinking garbage quality water that is legit making them more stupid.

lead poisoning causes brain damage.

it’s amazing. i am amazed.

and here i am, drinking the kool aid too.

plants do well enough but they don’t thrive in my yard, many of them die. sometimes i feel like E.T. empathically connected to my plants, our health mutually waxing and waning depending on how toxic our environment is. you know?

noise pollution also a problem. and now with COVID restrictions and everyone staying home, cabin fever. this feeling that i can’t walk more than 5 steps in any direction without banging into something or someone.

this is normal. this is to be expected. i’ve been living downtown for 20 years, in an entertainment district that vibrates with music and noise and crowds spilling onto the sidewalk every weekend. a slightly perceptible boom boom boom! in the air around us. i don’t necessarily mind this, the social noises, the loud music so long as it’s not too violent or repetitive, makes no difference to me. it’s all the added layers of noise pollution that grates on my nerves. loud vehicles. rush hour. people screaming at the top of their lungs just to hear themselves and each other. loud drunk people.

at least it’s not as bad as the Vieux Port with that dance club blaring music right off the water like that, so loud that you can both hear and feel the noise pollution along the shore in St-Lambert. i wonder how it affects the fish in the seaway. makes them swim sideways or some shit. like when you shine an artificial light sideways in a fish tank. affects their swim bladder. makes fish swim sideways. i’m not a fish expert but it’s a thing. look it up.

like a lot of other folks i used to mock people on the south shore who complained about noise pollution. but have gone biking along the paths there many times in the summer over the years and the music from across the St-Lawrence is almost always BOOMING, the south shore is inundated with noise pollution from les Terrasses Bonsecours in the Vieux Port. and music festivals on Ile Ste-Helene.

i love music and i love music festivals but if i lived near the lakeshore in St-Lambert, Brossard or Longueuil I’d be pissed as fuck at the noise pollution, especially if i had to get up early in the morning to work on the weekends. should be a better compromise there.

anyway. just an example, that our government or people in Quebec don’t take don’t noise pollution very seriously. that cracking down on noise pollution is an infringement rather than a benefit. even though noise pollution causes heart disease.

weird remnants of a masochistic Catholic culture in Quebec. indulging in self-punishment.

anyway.

i’m an outdoorsy person. i need more space. a recently renovated home. a bigger garden. a workshop. good water and air filtration. sound proofing. i absolutely love my neighbourhood and the folks in it but i need some room to breathe. it’s suffocating. insular. saps my creativity. i feel like i’m caged in…

i need to move to a less densely populated neighbourhood. not the suburbs but not downtown either. urban burbs.

urburbs?

yes indeed.

or something better than this.

Blackbird has spoken like the first bird

I am up early in the mornings now, consistently. Rolling out of bed at dawn has become my new lifestyle and I love it. Grew into it organically without forcing myself by listening to my body and what it needs as opposed to listening to my ego and doing what it wants, and now everything in my life is improving.

What do you call it when you’re in a state of arrested development and you start… developing… again?

Personal growth?

Sounds like a bacterial infection.

A new leaf

Do not look outside yourself for your leader

“You have been telling the people that this is the Eleventh Hour, now you must go back and tell the people that this is the Hour. And there are things to be considered . . .

Where are you living?

What are you doing?

What are your relationships?

Are you in right relation?

Where is your water?

Know your garden.

It is time to speak your Truth.

Create your community.

Be good to each other.

And do not look outside yourself for the leader.”

Then he clasped his hands together, smiled, and said, “This could be a good time!”

“There is a river flowing now very fast. It is so great and swift that there are those who will be afraid. They will try to hold on to the shore. They will feel they are torn apart and will suffer greatly.

“Know the river has its destination. The elders say we must let go of the shore, push off into the middle of the river, keep our eyes open, and our heads above water. And I say, see who is in there with you and celebrate. At this time in history, we are to take nothing personally, Least of all ourselves. For the moment that we do, our spiritual growth and journey comes to a halt.

“The time for the lone wolf is over. Gather yourselves! Banish the word struggle from you attitude and your vocabulary. All that we do now must be done in a sacred manner and in celebration.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.”

— attributed to an unnamed Hopi elder

Hopi Nation

Oraibi, Arizona

mont royal

Quebec City 2015